The Doppler effect. What is it really? Well you can thank our friend Doppler for the classic “VroooOOOmm” noise a car makes as it drives passed you. Where the “Vroo” sounds high pitched as the car approaches, sounds “oO” as it is directly next to you, and finishes with a low pitch “OOmm” as it drives away from you. Have you ever wondered why a car does that? I mean when you are in the car, it’s not as if you constantly hear “VroooOOOmm” as you drive passed people on the side walk.

This article aims to clear up the idea of the Doppler effect so that we all hopefully have a fairly intuitive understanding of how and why it occurs.

Perfect Pitch

What is sound? Well, sound is a vibration through the air. Once the vibration hits your ear, your brain interprets those pressure waves as a noise. Where pressure waves that vibrate faster are interpreted with a higher pitch, and slower pressure waves with a lower pitch. The speed of this vibration is known as a frequency and it turns out that we can listen to a pure frequency wave (although it sounds awful) however, noises that we encounter in day to day life are actually combinations, sums, of multiple pure frequency waves. Our friend Fourier has quite a bit to say on this topic, and I am sure I will encounter it again in future articles.

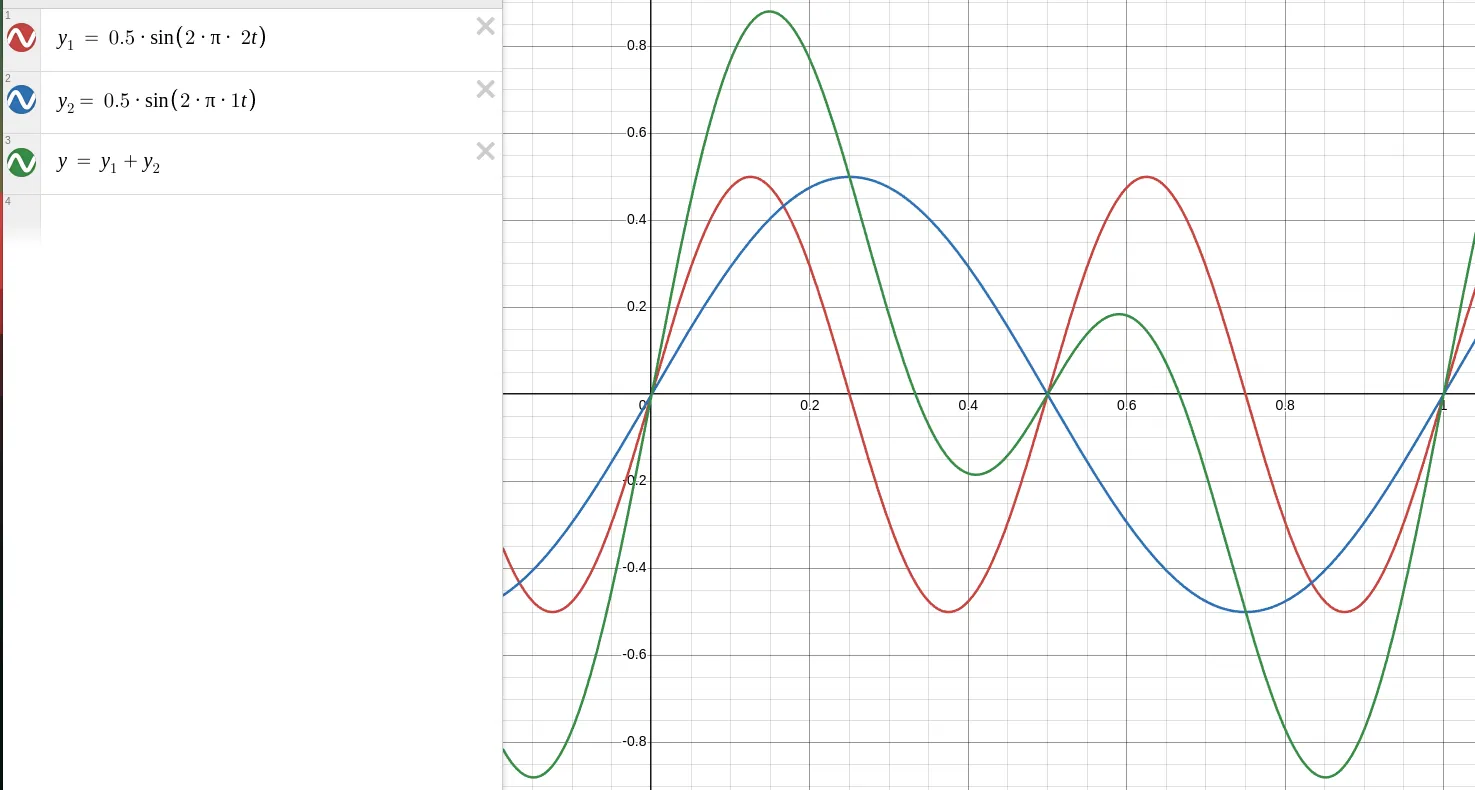

An example of this can be seen below, where the red wave is a 1Hz pure sound, the blue is a 2Hz pure sound and what you would hear (if you could hear frequencies that low) would be the green waveform.

This seems off topic but it actually is a key piece of information we need to understand the Doppler effect. Notice the red wave is much more “squished” together horizontally than the blue one is. That is because it is at a higher frequency. So if we bring this back to the idea of a car driving passed, we see that the wave’s we hear (the sound) must go from being more “squished” (higher frequency) as a car approaches us and transitions to less “squished” (lower frequency) as the car drives away from us.

It’s All Relative…

This is the exact definition of the Doppler effect. The frequency change that occurs from motion. In fact more, importantly, relative motion. When you are sitting in a car, you don’t hear the frequency of the engine changing as you drive along with it. That is because relative to the engine (the noise transmitter), you are not moving. Even at 100km/h, the position of the engine relative to you, never changes which in turn means the frequency doesn’t change.

So now we have a rough understanding (pun intended) of what the sound wave is doing as a car travels passed us. Why does the frequency/pitch do that?

Well if we first imagine that a sound wave is a stream of paintballs coming out of a paintball gun, if we aren’t moving then we feel the paintballs hit us once a second. However, if we run directly towards the paintball gun (which is not a great idea by the way), then we would travel some distance towards the paintball gun before the next paintball reaches us. This would mean it would hit us sooner, seeing as it did not need to travel as far. So we may experience the paintball hitting us once every 0.9 seconds instead of the once a second previously. Similarly, if we run away from the paintball gun (a very good idea) then we make the paintball have to travel an extra distance before it hits us. This would take longer which means we may experience it hitting us once every 1.1 seconds. This is assuming we run at a perfectly regular velocity.

Well the same analogy can be used to think of the frequency changes that happen due to the Doppler effect. I have made a small animation that shows what I am referring to below. Imagine that the yellow triangle is a sound transmitter, and the red is a receiver (your ear) moving towards the sound source, away from it, or staying still. The red receiver plots a point inside it every time it hits a sound “particle”. (The code that created the Doppler effect animation can be found here)

To replay the animation you can hit ‘r’ on your keyboard, otherwise it will loop every 10 seconds.

Notice that the sound never actually changes frequency, it is purely the observer who records a change in frequency, either higher pitch when travelling towards the transmitter or lower pitch when travelling away.

What’s the Use?

So now that we understand how the Doppler effect works. What can we do with it?

Well it turns out that light also travels as a wave and not only that, it actually is impacted by the Doppler effect in the same way. Just that rather than the speed of sound at ~350 metres per second we are talking more like ~300,000 kilometres per second.

Luckily humans have come up with some very clever and very accurate methods of measuring frequencies. Thanks to our new friend Doppler we also now know that there is a relationship between measured frequency and relative motion. So by simply measuring the change in light frequencies from a moving object we can tell how fast it is moving and whether it is towards us or away from us.

These frequency shifts aren’t always appreciated though, in wireless communication such as Wi-Fi or cellular signals data is sent over channels that are at very specific frequencies (hand waving a bit here). If you phone measures that frequency to be different when you hop in a car vs when you are stationary then it causes some trouble with transmitting data reliably. So your phone, the Wi-Fi router or the base station you are connected to must account for these Doppler changes accordingly so that the sent data and the data that is received is the same.

Some examples of places where the Doppler effect is used include:

- Measuring blood flow in veins or in the heart

- Measuring the motion of planets

- Police speed radar

- Meteorological measurements (storm movements)

- The VroooOOOmm sound a car makes

Thanks so much for your time and I hope that you enjoyed!